We sat down with composer Tomás Gueglio and harpist Ben Melsky to talk a bit about Tomás’s new work Proa and working with dancers from Delfos Danza Contemporánea.

Tell us about the piece. What are the metaphorical and aesthetic materials that you’re interested in exploring in Proa?

T: Proa will be a piece for four dancers, harp, and piano (without pianist) lasting approximately 30 minutes. The sound world I am imagining is in line with my current tendency of writing immersive textures and landscapes. The work is still in the early stages of the composition, but in the initial conversations with Claudia (choreographer) and Ben we came up with a few guiding concepts to use as jumping-off points. Some of these concepts refer to common tropes in music and dance (water, lyre...) but others connect to issues that are not as picturesque.

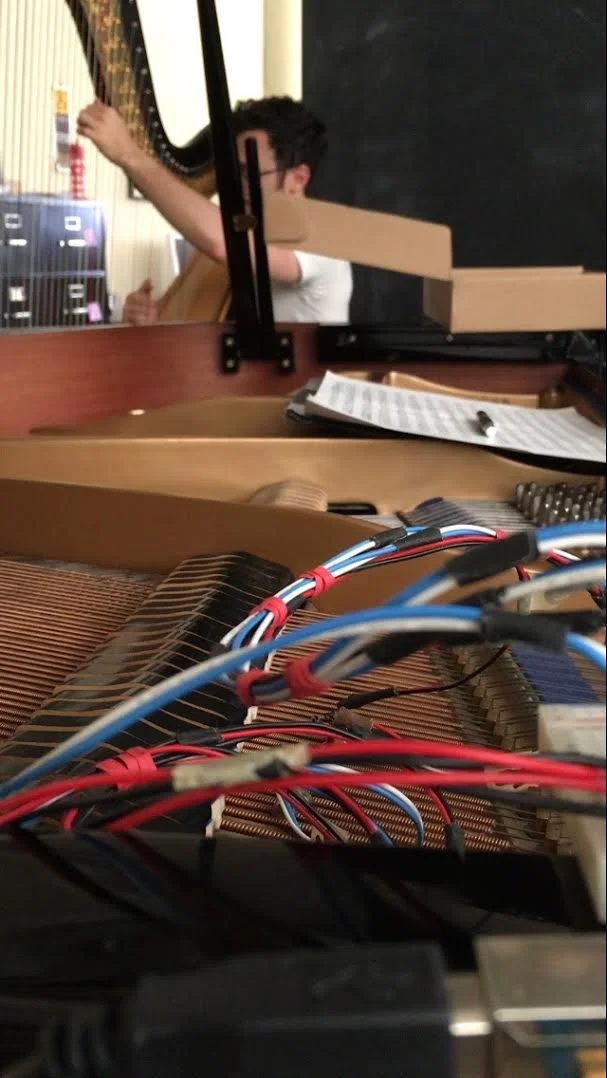

What interests you about joining the harp (played by a live harpist - Ben) and piano (controlled by vibrating cell phone attachments in the strings)?

T: This goes back to the previous question. After talking to Claudia, I began to picture an overall sound for the piece. It occurred to me that, to realize that sound, I could start experimenting with samples of two previous works of mine: the second movement of a piece for solo harp, Felt, and my Nokia Etude #3, which is a work for piano that employs a device made of cell phone motors. Both pieces are quite textural and I had the suspicion that they could mix well, with the piano providing further nuance and complexity to an already rich harp resonance. I also like the theatrical idea of having two instruments on stage with one of them being played by an invisible performer. I think it goes well with the poetics of the piece.

Working with dancers (or with actors or other types of artists) often brings a categorically different approach to the rehearsal process. Can you speak to your past experience working with artists across disciplines and how the rehearsal process produced a different result?

T: I would say the approach varies depending on the specifics of the project and the group of people working on it. Regarding the rehearsal process, my default attitude is to defer to the disciplinary idiosyncrasies of the people I am working with. The do’s and dont’s of rehearsing with, say, actors are different from the ones of rehearsing with musicians and I try to be respectful of that. In the case of my previous collaboration with Delfos, the final product was the result of a series of improv sessions where there was not a clear compartmentalization between composing, choreographing, rehearsing, and performing. They all happened somewhat simultaneously.

B: Most music performances follow the same general script - you prepare your part, show up at the first rehearsal (often just a few days before the performance) rehearse intensely for a few hours a few times and then perform. Working with dancers or actors is a very different approach; the group learns the work together rather than individual learning fastened together in rehearsal. Musicians’ training often means that one’s part should be basically performance-ready by day one. By comparison, in theater or dance on day one you really don’t know too much about the final result. The journey from start to finish is a long, complicated, often more vulnerable one.

I think another important thing that musicians can learn from this rehearsal approach is actually how it relates to performances. By habit, we’re quite used to the general premise of a single performance. Multiple performances offer a sense of fluidity and development within the performance cycle itself. A show will change and evolve over the course of several performances, offering opportunities to discover different moments or ideas within the piece.

In past work (On Love, After L’Addio, String Quartet...) you engage with historical texts or refer to outside source material. What interests you about that dialogue and do you anticipate similar treatment of outside material here?

T: I believe it is more parasitism than dialogue but yes, this engagement with historical texts is a recurrent feature in what I do. Following this line of thought, I would say my interest in intertext is quite utilitarian, in that the borrowed material provides a referential anchorage out of which one can unfold a chain of materials and associations. For Proa, I am considering using some borrowed music but the amount of texts that can relate to things like ‘water’ or ‘lyre’ is so vast that I am having a hard time deciding. In any case, I know that if I end up working with pre-existing music there is a strong possibility that the borrowed material will encapsulate features that are not necessarily present in the music that is not new, like a negative image of the not-borrowed music.

How do you feel about having more of a role of composer/improvisor throughout the collaborative process? How do you feel about being onstage with the dancers?

B: This is kind of a new thing for me. While there is always a sense of improvisation and play working in individual composer sessions, I think this will be more than a bit different, if for no other reason than there will be one harpist, one composer, and four dancers all working together. I’m eager to see how ideas translate between the mediums, how the dancers interpret timbre, harmony, texture, etc. into their work and how watching their process will change my perspective of sound and its function within the piece. The Delfos dancers are first and foremost improvisers, so I am eager to see how we learn to anticipate each other’s moves and coordinate throughout.

Links:

Nokia Etude #3 https://vimeo.com/123471987

Poster design by Santiago Fernandez